"Healthy rituals help us feel better about ourselves; addictive rituals make us feel worse about ourselves."

Other titles you may like.

Addictive Thinking:

Understanding Self-Deception

First-Year Sobriety: When All

That Changes Is Everything

Visit Recovery Road to view and

listen to all the episodes.

Episode 131 -- July 15, 2021

Addictive Rituals

Rituals are a source of comfort. Those of us in recovery used to have our way of doing things, especially when it came to our addictions—ways we kept our substance use hidden or safe or secret. These rituals protected us, helping us respond to stress or conflict in our lives. They also protected our addictions, because the substances were the answer every time. But what happens now that we're in recovery? How can we undo damaging patterns and develop rituals that help instead of hurt us?

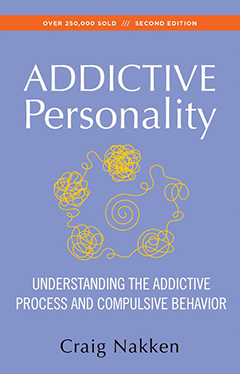

In his book The Addictive Personality: Understanding the Addictive Process and Compulsive Behavior, Craig Nakken describes the two-sided personality we developed through our addiction and offers insights that can begin to answer a few of our big, deep, and scary questions about how our addictions came to be and how our old patterns continue to affect us in recovery. In this excerpt, Nakken helps us see how the important human activity of ritual-building was used by our addiction to keep us isolated, and how we can choose recovery rituals that help us find connection and community.

This excerpt has been edited for brevity.

Rituals are important for many reasons. Rituals help to bind us to our beliefs and values and connect us to others with similar beliefs and values. We reassure ourselves of our beliefs and values through our use of rituals. Whenever we are involved in a ritual, it will strengthen our ties to whatever it represents.

Erich Fromm states in his book The Sane Society that in a ritual, a person "acts out with his body what he thinks out with his brain." Rituals are value statements. In addiction, rituals become value statements about the beliefs of the Addict. These rituals can be, and often are, totally opposite from the beliefs of the Self. Therefore, in addiction, the addicted person acts out with his or her body the addictive logic existing in the brain.

Rituals are a form of language—a language of behavior. Rituals speak about our faith and about our current beliefs and values, either positive or negative. For example, participating in the ritual of a family birthday party can help tie us to our family. Many aspects of this ritual are predictable: who will arrive on time and who will arrive late, who will make the dumb jokes at the wrong times, and who will engage in serious conversation. Our involvement in this ritual becomes a statement, especially to ourselves about what we believe is important. Even if we don't want to participate, we feel it's important that we do. We have acted "right" by taking part.

Our actions also are prescribed by the ritual itself. When the ritual is a birthday party, people sing "Happy Birthday," smile, make certain comments to the person having the birthday, bring presents, and eat certain foods.

When addicts are involved in addictive rituals and behaviors, they, too, act in prescribed ways. They are making behavioral statements that support the addictive process and addictive belief system, just as attending a family birthday party is making a behavioral statement in support of one's family and the family's belief system.

Besides binding us to beliefs and values and to others with similar beliefs, rituals bring us comfort because they are predictable. Rituals are based on consistency: first you do this; then you do that. The comfort may not always be apparent, but it is there. When the sequence of the ritual is changed or part of the sequence is left out, we experience discomfort. Addicts ritualize their behavior for the comfort found in predictability. Addicts also ritualize their actions around behaviors they find exciting; they feel comfortable knowing the excitement will be there if they act in certain ways.

Rituals bring us comfort at times of crisis or during times of conflict. By engaging in ritualized behavior, we are brought back to our beliefs and experience the comfort that we find within them. When our lives are in turmoil, we tend to seek out consistency and familiarity. Addicts do the same: when they face crisis and stress, they run to the comfort they find in their rituals. Addictive rites tie them not only to a belief or value but also to a mood—a feeling in which they've come to have faith and find comfort.

Rituals are statements about what people have faith in. Addicts no longer put faith in people, but in their addictive rite. Each part of the rite is important to the Addict and is designed to heighten the mood change.

Choices and Rituals

It is through our rituals and the faith we have in them that we hope to solve the internal conflict we feel when we are faced with choices. When facing a choice, a person with an addiction feels a great tension inside: Do I act out or don't I act out? This tension can go on for hours, days, or weeks at a time and is a large part of the suffering caused by addiction. The addictive ritual will ease this tension, for when an addict is involved in a ritual, this conflict is momentarily over; a choice has been made, and there is a sense of release.

Addicts may then face a different type of stress or tension, one caused by the shame of acting out. But the internal tension of do I act out or don't I? has been solved for the moment. This release of tension and the resulting sense of peace help to reinforce the choosing of the addictive process. This is called negative surrendering. No matter the outcome, the surrender provides a temporary relief from any tension between the Addict and the Self. Both the tension and the need for release will happen again, and so, too, will the negative surrender.

Developing Healthy Rituals

All addicts develop some form of rigid ritualistic acting out. It is important for recovering people to understand their Addict has preferred ways of acting out, and there are danger areas, times, and behaviors they need to avoid. A recovering spending addict who has a ritual of acting out on Friday evenings will need to make sure he is around safe friends doing safe activities on Friday nights for some time to come. A sex addict who cruised a certain part of town as part of her addictive ritual will need to stay away from that part of town.

Healthy rituals bind us to others, to family or friends, to helpful spiritual principles, or to a community based on helping each other. In this sense, addictive rituals are reverse rituals: their primary purpose is to isolate us from others. Healthy rituals help us feel better about ourselves; addictive rituals make us feel worse about ourselves. Healthy rituals bind us to people who care for us; addictive rituals bind us to the Addict or the dangerous side of others. Healthy rituals help us have better relationships; addictive rituals destroy relationships. Healthy rituals help us to feel pride about ourselves and friends; addictive rituals cause shame. Healthy rituals are about celebrating life; addictive rituals seek out death.

About the Author:

Craig M. Nakken, MSW, CCDP, LCSW, LMFT, is a lecturer, trainer, and family therapist specializing in the treatment of addiction. With decades of working experience in the areas of addiction and recovery, Nakken has a private therapy practice in St. Paul, Minnesota.

He is the author of several seminal books and writings in the recovery field, including Men's Issues in Recovery, Reclaim Your Family from Addiction, and Finding Your Moral Compass.

© 1988, 1996 by Hazelden Foundation

All rights reserved