"When I pause before reacting, it seems to stimulate the "don't be a jerk" lobe of my brain, and I come up with a better plan."

Other titles you may like.

A Place Called Self:

Women, Sobriety and Radical Transformation

The 12 Steps Unplugged:

A Young Peron's Guide to Alcoholics Anonymous

Visit Recovery Road to view and

listen to all the episodes.

Episode 244 -- October 27, 2022

How to Not Be a Jerk

Every problem has its root. We know that there were some foundational problems that drove us to addiction. Maybe we began to use substances to cope with struggles at work, self-deprecating thoughts or traumatic events that happened to us as a child. And although we are now in recovery, we still may have to address the issues that prompted our compulsive behaviors to begin with. This time we have the tools and the support we need to tackle these problems head on.

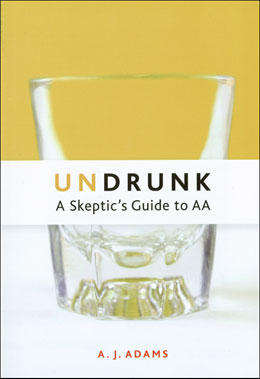

In Undrunk: A Skeptic's Guide to AA, recovering alcoholic A.J. Adams shares insights and wisdom from his own story of skeptic spirituality, and the gifts of acceptance and willingness that he found along the path of recovery.

In this excerpt, the author describes the feelings of pride and complacency that can develop as we start to find success in the Program and shares how these feelings started to show up in his everyday life. From Adams' story, we can learn how Step Ten can help slow us down and even put a stop to behaviors that can threaten our sobriety. Working through our emotions frees us to continue our day and enjoy our recovery.

This excerpt has been edited for brevity.

I don't like the term "maintenance Steps," which sounds like an oil change. I think the final three Steps are the trifecta of sobriety and the real payoff for doing the previous nine. Steps 10, 11, and 12 showed me how to incorporate AA into my daily life as a personal code that keeps me sober and happy.

By the time I got to Step 10, I was starting to feel very good about life in general and about my life in particular. I wanted to keep things going that way, and Step 10 would be an important part of that. In Step 4, I made a "fearless moral inventory" of myself. Step 10 is a mini version of Step 4. It's much less comprehensive and, once I got the hang of it, not half as hard as remembering where I parked my car used to be.

Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

Threats to my newfound sobriety seem to come from two general directions: pride and complacency. This is not true for everyone, but these two seem to pop up in many AAs' sober lives. The downside of success in working the Steps can be the success itself. I have to admit that pride shaded almost everything I did in my early recovery. By the end of rehab, I was proud that I'd finally taken the plunge. I was proud of my diligence in working the Steps. I believed that I deserved the improvements in my life. I don't think any of that is really bad. As long as I realized that giving myself sole credit for my progress was nonsense, I was okay. I needed motivation to work the Steps thoroughly, and if self-satisfaction helped do the trick, so be it.

I also believe that some complacency is normal after you've completed your first run through the Steps. There was no way I could sustain the degree of emotional and intellectual focus on my recovery that I had mustered in rehab and while doing the Steps. There had to be a fifth gear, and I wanted to find it. I needed something that would keep me in continuous touch with the program without overwhelming my life. Think of the thermostat in your house: you don't look at it every ten minutes, but if you feel a little cold or a little hot, it's very useful. Step 10 is my thermostat. Here's how it works.

One day, not long after finishing the Steps (or at least my first set), I was at the gym working on the physical me. I was waiting for a piece of equipment to come open and noticed that as the previous user left, she didn't wipe it off with the antibiotic spray. There was no doubt in my mind that I was best positioned to ward off this emerging public health crisis. Confident that I was calm enough for the job, I asked her whether she planned to disinfect the equipment. She took this as an entirely inappropriate criticism of her personal hygiene and let me have it. I lost control immediately and returned fire. Both of us stormed out very upset, and the equipment remained a seething cauldron of bacteria.

I was concerned about my loss of temper, so I shared the episode with my sponsor. (By this time, I was becoming convinced that the key to effective sponsoring was an ability to nod in a wise way.) After some nodding, punctuated by raised eyebrows and a small smirk, my sponsor counseled, "Might want to try Tenth-Stepping things like this."

The advice resonated and has helped me learn to trust my instincts in two new ways. First, if I think I may have hurt another person in some way, I admit it to the injured party and try to set things right on the spot. If for some reason I can't do that, at least I accept my part in the way things went. This takes only a few minutes in most cases, and poof, the bad feeling's gone and I move on. Second, I'm learning to pause before responding to every little thing. I recently read about a study that showed that pauses in symphonic music stimulate a creative part of the brain—not the music, the pauses. I think that might be true. When I pause before reacting, it seems to stimulate the "don't be a jerk" lobe of my brain, and I come up with a better plan.

Bill Wilson counseled that alcoholics should probably leave righteous indignation to people who can handle it. I couldn't agree more.

About the Author:

A. J. Adams, a recovering alcoholic, consults, writes, and teaches. He lives with his wife in the Southwest. A. J. Adams is a pen name.

© 2009

All rights reserved